GI resistance in the Vietnam war

History of the widespread mutiny of US troops in Vietnam that brought the world's most powerful military machine to its knees. The GI anti-war movement within the army was one of the decisive factors in ending the war.

An American soldier in a hospital explained how he was wounded: He said

“I was told that the way to tell a hostile Vietnamese from a friendly Vietnamese was to shout ‘To hell with Ho Chi Minh!’ If he shoots, he’s unfriendly. So I saw this dude and yelled ‘To hell with Ho Chi Minh!’ and he yelled back, ‘To hell with President Johnson!’ We were shaking hands when a truck hit us.”

- from 1,001 Ways to Beat the Draft, by Tuli Kupferburg.

The U.S. government would be happy to see the history of the Vietnam War buried and forgotten. Not least because it saw the world’s greatest superpower defeated by a peasant army, but mainly because of what defeated the war effort – the collective resistance of the enlisted men and women in the U.S. armed forces, who mutinied, sabotaged, shirked, fragged and smoked their way to a full withdrawal and an end to the conflict.

Before the war

Military morale was considered high before the war began. In fact, the pre-Vietnam Army was considered the best the United States had ever put into the field. Consequently, the military high command was taken quite by surprise by the rapid disintegration of the very foundations of their power.

Military morale was considered high before the war began. In fact, the pre-Vietnam Army was considered the best the United States had ever put into the field. Consequently, the military high command was taken quite by surprise by the rapid disintegration of the very foundations of their power.

As American presence reached major proportions in 1964 and 1965, people joining the military were predominantly poor working class whites or from ethnic minorities. University attendance and draft resistance saved many better-off young white people from the draft, and many other less privileged workers signed up in order to avoid a prison term, or simply due to the promises of a secure job and specialist training.

The image these young people had of life in the military was shattered quite rapidly by the harsh reality they faced.

Those who had enlisted found that the promises made by recruiters vanished into thin air once they were in boot camp. Guarantees of special training and choice assignments were simply swept away. This is a fairly standard procedure used to snare enlistees. In fact, the military regulations state that only the enlistee, not the military, is bound by the specifics of the recruiting contract. In addition, both enlistees and draftees faced the daily harassment, the brutal de-personalisation, and ultimately the dangers and meaninglessness of the endless ground war in Vietnam. These pressures were particularly intense for non-white GIs, most of whom were affected by the rising black consciousness and a heightened awareness of their oppression.

These forces combined to produce the disintegration of the Vietnam era military. This disintegration developed slowly, but once it reached a general level it became epidemic in its proportions. In its midst developed a conscious and organised resistance, which both furthered the disintegration and attempted to channel it in a political direction.

1966 - The resistance begins

1966 - The resistance beginsThe years 1966 and 1967 saw the first acts of resistance among GIs. Given the general passivity within the ranks and the tight control exercised by the brass, these first acts required a clear willingness for self-sacrifice. For the most part they were initiated by men who had had some concrete link with the left prior to their entrance into the military.

The first major public act of resistance was the refusal, in June of 1966, of three privates from Fort Hood, Texas to ship out to Vietnam. The three men, David Samas, James Johnson, and Dennis Mora, had just completed training and were on leave before their scheduled departure for the war zone. The case received wide publicity, but the men were each eventually sentenced to three years at hard labour.

There followed a series of other individual acts of resistance. Ronald Lockman, a black GI refused orders to Vietnam with the slogan, "I follow the Fort Hood Three. Who will follow me?" Capt. Howard Levy refused to teach medicine to the Green Berets, and Capt. Dale Noyd refused to give flying instructions to prospective bombing pilots. These acts were mostly carried out by existing left-wingers, and were consciously geared toward political resistance. However there was also in this period the beginning of an ethical and/or religious resistance. The first clear incident occurred at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, where in April of 1967 five GIs staged a pray-in for peace on base. Two of these GIs refused a direct order to cease praying and were subsequently court-marshalled.

The majority of these early instances of resistance were actually simply acts of refusal; refusal to go to Vietnam, to carry out training, to obey orders. They were important in that they helped to directly confront the intense fear which all GIs feel; they helped to shake up the general milieu of passivity. But the military was quite willing to deal with the small number of GIs who might put their heads on the chopping block; to really affect the military machine would require a more general rebellion.

1968 – Collapse of morale

Up until 1968 the desertion rate for U.S. troops in Vietnam was still lower than in previous wars. But by 1969 the desertion rate had increased fourfold. This wasn’t limited to Southeast Asia; desertion rates among GIs were on the increase worldwide. For soldiers in the combat zone, insubordination became an important part of avoiding horrible injury or death. As early as mid-1969, an entire company of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade sat down on the battlefield. Later that year, a rifle company from the famed 1st Air Cavalry Division flatly refused - on CBS TV - to advance down a dangerous trail. In the following 12 months the 1st Air Cavalry notched up 35 combat refusals.

1968 – Collapse of morale

Up until 1968 the desertion rate for U.S. troops in Vietnam was still lower than in previous wars. But by 1969 the desertion rate had increased fourfold. This wasn’t limited to Southeast Asia; desertion rates among GIs were on the increase worldwide. For soldiers in the combat zone, insubordination became an important part of avoiding horrible injury or death. As early as mid-1969, an entire company of the 196th Light Infantry Brigade sat down on the battlefield. Later that year, a rifle company from the famed 1st Air Cavalry Division flatly refused - on CBS TV - to advance down a dangerous trail. In the following 12 months the 1st Air Cavalry notched up 35 combat refusals.

The period from 1968 to 1970 was a period of rapid disintegration of morale and widespread rebelliousness within the U.S. military. There were a variety of causes contributing to this development. By this time the war had become vastly unpopular in the general society, anti-war demonstrations were large and to some degree respectable, and prominent politicians were speaking out against the continuation of the war. For a youth entering the military in these years the war was already a questionable proposition, and with the ground war raging and coffins coming home every day very few new recruits were enthusiastic about their situation. In addition, the rising level of black consciousness and the rapidly spreading dope culture both served to alienate new recruits from military authority. Thus, GIs came into uniform in this period with a fairly negative predisposition.

Their experience in the military and in the war transformed this negative pre-disposition into outright hostility. The nature of the war certainly accelerated this disaffection; a seemingly endless ground war against an often invisible enemy, with the mass of people often openly hostile, in support of a government both unpopular and corrupt. The Vietnamese revolutionaries also made attempts to reach out to American GIs, with some impact.

From mild forms of political protest and disobedience of war orders, the resistance among the ground troops grew into a massive and widespread “quasi-mutiny” by 1970 and 1971. Soldiers went on “search and avoid” missions, intentionally skirting clashes with the Vietnamese, and often holding three-day-long pot parties instead of fighting.

Clampdown and repercussions

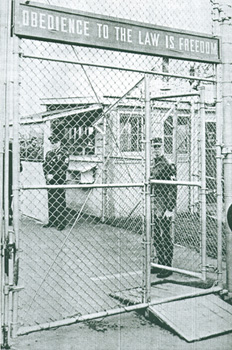

Clampdown and repercussionsInitially response to mutinous behaviour was swift and harsh. Two black marines, William Harvey and George Daniels, were sentenced to six and ten years at hard labour for speaking against the war in their barracks. Privates Dam Amick and Ken Stolte were sentenced to four years for distributing a leaflet. Ford Ord. Pvt. Theoda Lester was sentenced to three years for refusing to cut his Afro. And Pvt. Wade Carson was sentenced to six months for "intention" to distribute underground newspaper FED-UP on Fort Lewis. The pattern was widespread and the message was clear: the brass was not about to tolerate political dissent in its ranks.

However, as the war progressed the stockades (military prisons) became over-crowded with AWOLs and laced with political organisers. In July of 1968 prisoners seized control of the stockade at Fort Bragg and held it for three days, and in June of 1969 prisoners rebelled in the Fort Dix stockade and inflicted extensive damage before being brought under control. Probably the most famous incident of stockade resistance occurred at the Presidio, where 27 prisoners staged a sit-down during morning formation to protest the shot-gun slaying of a fellow prisoner by a stockade guard. The men were charged with mutiny and initially received very heavy sentences, but their sacrifice had considerable impact around the country. After a year their sentences were reduced to time served.

A number of factors eventually helped to weaken the brass’s repressive power. Media coverage, public protest, and the general growth of GI resistance all played a part. The key factor though was that political GIs continued to be dangerous in the stockades, and eventually the military often chose to discharge dissidents and get rid of them all together.

1970 - The rebellion grows

By 1970, the U.S. Army had 65,643 deserters, roughly the equivalent of four infantry divisions. In an article published in the Armed Forces Journal (June 7, 1971), Marine Colonel Robert D. Heinl Jr., a veteran combat commander with over 27 years experience in the Marines, and the author of Soldiers Of The Sea, a definitive history of the Marine Corps, wrote:

By 1970, the U.S. Army had 65,643 deserters, roughly the equivalent of four infantry divisions. In an article published in the Armed Forces Journal (June 7, 1971), Marine Colonel Robert D. Heinl Jr., a veteran combat commander with over 27 years experience in the Marines, and the author of Soldiers Of The Sea, a definitive history of the Marine Corps, wrote:

“By every conceivable indicator, our army that remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse, with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug-ridden, and dispirited where not near mutinous. Elsewhere than Vietnam, the situation is nearly as serious… Sedition, coupled with disaffection from within the ranks, and externally fomented with an audacity and intensity previously inconceivable, infest the Armed Services...”

Heinl cited a New York Times article which quoted an enlisted man saying, “The American garrisons on the larger bases are virtually disarmed. The lifers have taken our weapons away...there have also been quite a few frag incidents in the battalion.”

“Frag incidents” or “fragging” was soldier slang in Vietnam for the killing of strict, unpopular and aggressive officers and NCO’s (Non-Commissioned Officers, or “non-coms”). The word apparently originated from enlisted men using fragmentation grenades to off commanders. Heinl wrote, “Bounties, raised by common subscription in amounts running anywhere from $50 to $1,000, have been widely reported put on the heads of leaders who the privates and SP4s want to rub out.” Shortly after the costly assault on Hamburger Hill in mid-1969, one of the GI underground newspapers in Vietnam, GI Says, publicly offered a $10,000 bounty on Lieutenant Colonel Weldon Hunnicutt, the officer who ordered and led the attack.

“The Pentagon has now disclosed that fraggings in 1970 (209 killings) have more than doubled those of the previous year (96 killings). Word of the deaths of officers will bring cheers at troop movies or in bivouacs of certain units.” Congressional hearings on fraggings held in 1973 estimated that roughly 3% of officer and non-com deaths in Vietnam between 1961 and 1972 were a result of fraggings. But these figures were only for killings committed with grenades, and didn’t include officer deaths from automatic weapons fire, handguns and knifings. The Army’s Judge Advocate General’s Corps estimated that only 10% of fragging attempts resulted in anyone going to trial. In the America l Division, plagued by poor morale, fraggings during 1971 were estimated to be running around one a week. War equipment was frequently sabotaged and destroyed.

Drug use was epidemic, with an estimated 80% of the troops in Vietnam using some form of drug. Sometime in mid-1970 huge quantities of heroin were dumped on the black market, and GIs were receptive to its enveloping high. By the end of 1971 over 30% of the combat troops were on smack.

Drug use was epidemic, with an estimated 80% of the troops in Vietnam using some form of drug. Sometime in mid-1970 huge quantities of heroin were dumped on the black market, and GIs were receptive to its enveloping high. By the end of 1971 over 30% of the combat troops were on smack.

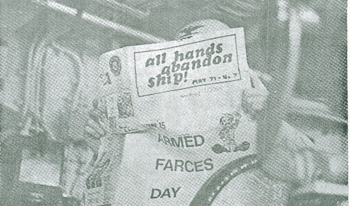

By 1972 roughly 300 anti-war and anti-military newspapers, with names like Harass the Brass, All Hands Abandon Ship and Star Spangled Bummer had been put out by enlisted people. Many hundreds of GIs created these papers, but their influence was far wider, with thousands more who helped distribute them, and tens of thousands of readers. Riots and anti-war demonstrations took place on bases in Asia, Europe and in the United States.

The situation stateside was less intense but no less disturbing to the military brass. Desertion and AWOL became absolutely epidemic. In 1966 the desertion rate was 14.7 per thousand, in 1968 it was 26.2 per thousand, and by 1970 it had risen to 52.3 per thousand; AWOL was so common that by the height of the war one GI went AWOL every three minutes. From January of '67 to January of '72 a total of 354,112 GIs left their posts without permission, and at the time of the signing of the peace accords 98,324 were still missing.

The new air war, and the new resistance

By the early 1970s the government had to begin pulling out of the ground war and switching to an “air war,” in part because many of the ground troops who were supposed to do the fighting were hamstringing the world’s mightiest military force by their sabotage and resistance.

By the early 1970s the government had to begin pulling out of the ground war and switching to an “air war,” in part because many of the ground troops who were supposed to do the fighting were hamstringing the world’s mightiest military force by their sabotage and resistance.

With this shift, the Navy became an important centre of resistance to the war, primarily among crews on Navy attack carriers directly involved in the bombing. While there was dissidence and some political organising among Air Force personnel and in other parts of the Navy, it was where the support crews most directly touched the war that resistance flared. Probably the most dramatic incident occurred aboard the Navy attack carrier USS Coral Sea in the fall of 1971. The Coral Sea was docked in California while it prepared for a tour of bombing duty off the coast of Vietnam. On board was a crew of 4,500 men, a few hundred of whom were pilots, the rest being support crew. A handful of men on the ship began circulating a petition which read in part, "We the people must guide the government and not allow the government to guide us! The Coral Sea is scheduled for Vietnam in November. This does not have to be a fact. The ship can be prevented from taking an active part in the conflict if we the majority voice our opinion that we do not believe in the Vietnam war. If you feel that the Coral Sea should not go to Vietnam, voice your opinion by signing this petition."

Though the petition had to be circulated secretly, and though men took a calculated risk putting their name down on something which the brass might eventually see, within a few weeks over 1,000 men had signed it. Out of this grew an on-ship organisation called "Stop Our Ship" (SOS). The men engaged in a series of demonstrations to halt their sailing date, and on November 6 over 300 men from the ship led the autumn anti-war march in San Francisco, Their effort to stop the ship failed, and a number of men jumped ship as the Coral Sea left for Vietnam. But the SOS movement spread to other attack carriers, including the USS Hancock and the USS Ranger.

The Navy continued to be racked by political organising and severe racial unrest. Sometimes, black and white sailors would rebel together. The most significant of these took place on board the USS Constellation off Southern California, in November 1972. In response to a threat of less-than-honourable discharges against several black sailors, a group of over 100 black and white sailors staged a day-and-a-half long sit-in. Fearful of losing control of his ship at sea to full-scale mutiny, the ship’s commander brought the Constellation back to San Diego.* One hundred and thirty-two sailors were allowed to go ashore. They refused orders to re-board the ship several days later, staging a defiant dockside strike on the morning of November 9. In spite of the seriousness of the rebellion, not one of the sailors involved was arrested.

Sabotage was an extremely useful tactic. On May 26, 1970, the USS Anderson was preparing to steam from San Diego to Vietnam. But someone had dropped nuts, bolts and chains down the main gear shaft. A major breakdown occurred, resulting in thousands of dollars worth of damage and a delay of several weeks. Several sailors were charged, but because of a lack of evidence the case was dismissed. With the escalation of naval involvement in the war the level of sabotage grew.

In June of 1972 the USS Ranger was disabled by sabotage, and in October both the USS Kittyhawk and the USS Hassayampa were swept by fighting. In July, within the space of three weeks, two of the Navy’s aircraft carriers were put out of commission by sabotage. On July 10, a massive fire swept through the Admiral’s quarters and radar centre of the USS Forestall, causing over $7 million in damage. This delayed the ship’s deployment for over two months. In late July, the USS Ranger was docked at Alameda, California. Just days before the ship’s scheduled departure for Vietnam, a paint-scraper and two 12-inch bolts were inserted into the number-four-engine reduction gears causing nearly $1 million in damage and forcing a three-and-a-half month delay in operations for extensive repairs. The sailor charged in the case was acquitted. In other cases, sailors tossed equipment over the sides of ships while at sea.

Though the impact of these actions only slightly impeded the war effort, they helped to maintain a constant pressure on the Administration to withdraw the military from the disaster of the Indochina war.

The House Armed Services Committee summed up the crisis of rebellion in the Navy: “The U.S. Navy is now confronted with pressures...which, if not controlled, will surely destroy its enviable tradition of discipline. Recent instances of sabotage, riot, wilful disobedience of orders, and contempt for authority...are clear-cut symptoms of a dangerous deterioration of discipline.”

The makeup of resistance

The makeup of resistanceThere is a common misconception that it was draftees who were the most disaffected elements in the military. In fact, it was often enlistees who were most likely to engage in open rebellion. Draftees were only in for two years, went in expecting the worst, and generally kept their heads down until they got out of uniform. While of course many draftees went AWOL and engaged in group resistance when it developed, it was enlistees who were most angry and most likely to act on that anger. For one thing, enlistees were in for three or four years; even after a tour of duty in ‘Nam they still had a long stretch left in the service. For another thing, they went in with some expectations, generally with a recruiter's promise of training and a good job classification, often with an assurance that they wouldn't be sent to Vietnam. When these promises weren't kept, enlistees were very pissed off. A study commissioned by the Pentagon found that 64% of chronic AWOLs during the war years were enlistees, and that a high percentage were Vietnam vets. The following incident at a GI movement organising conference illustrates this point:

"A quick poll of the GIs and vets in the room showed that the vast majority of them had come from Regular Army, three or four year enlistments. Many of them expressed the notion that, in fact, it was the enlistees and not discontented draftees who had formed the core of the GI movement. A number of reasons were offered for this, including the fact many enlistees do enlist out of the hope of training, and a better job, or other material reasons. When the Army turns out to be a repressive and bankrupt institution, they are the most disillusioned and the most ready to fight back."

The official political Left attempted to involve itself in GI organising. Civilian counter-cultural coffee-shops were set up outside garrisons in the US to try to reach out to rank-and-file soldiers, with some limited success. Most left-wing parties proved themselves to be merely interested in recruitment or media-grabbing antics rather than sustained, long-term organising efforts which saw groups like the attempted American Servicemen’s Union disintegrate. Subsequently it was the troops themselves who organised their own resistance, driven by their own experiences of life in the Army.

However, the rebellion in the ranks didn’t emerge simply in response to battlefield conditions. A civilian anti-war movement in the U.S. had emerged on the coat tails of the civil rights movement, at a time when the pacifism-at-any-price tactics of civil rights leaders had reached their effective limit, and were being questioned by a younger, combative generation. Working class blacks and Latinos served in combat units out of all proportion to their numbers in American society, and groups such as the Black Panther Party, and major urban riots in Watts, Detroit and Newark had an explosive effect on the consciousness of these men. After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. major riots erupted in 181 U.S. cities; at that point the rulers of the United States were facing the gravest national crisis since the Civil War. And the radical movement of the late 1960s wasn’t limited to the United States. Large-scale rebellion was breaking out all over the world, in Latin American and Europe and Africa, and even against the Maoists in China. Its high points were the wildcat general strike that shut down France in May, 1968, and the near-state of insurrection in the 60s and 70s in Italy - the last time major industrialised democracies came close to social revolution.

Conclusion

The history of these olive-drab rebels is largely hidden from us, by rulers who would rather its lessons were forgotten. That the might of the most powerful military on Earth is worth naught if workers refuse to kill or oppress their fellow workers, and that the only allegiance which benefits us is not to our countries, our Generals, or to our flags, but to our class.

The history of these olive-drab rebels is largely hidden from us, by rulers who would rather its lessons were forgotten. That the might of the most powerful military on Earth is worth naught if workers refuse to kill or oppress their fellow workers, and that the only allegiance which benefits us is not to our countries, our Generals, or to our flags, but to our class.

Edited and altered by libcom from two articles, Harass the Brass: Some notes toward the subversion of the US armed forces and The Olive-Drab Rebels: Military Organising During The Vietnam Era by Matthew Rinaldi, both taken from prole.info.

* One source claimed that the USS Constellation was damaged by sabotage and brought to shore. If someone has any more information on this please let us know. All sources agreed on the dockside strike.

https://libcom.org/history/1961-1973-gi-resistance-in-the-vietnam-war

********************************

GI opposition to the Vietnam War, 1965-1973 - Howard Zinn

Historian Howard Zinn on the opposition to the Vietnam War by American soldiers.

The capacity for independent judgment among ordinary Americans is probably best shown by the swift development of antiwar feeling among American GIs-volunteers and draftees who came mostly from lower-income groups. There had been, earlier in American history, in stances of soldiers' disaffection from the war: isolated mutinies in the Revolutionary War, refusal of reenlistment in the midst of hostilities in the Mexican war, desertion and conscientious objection in World War I and World War II. But Vietnam produced opposition by soldiers and veterans on a scale, and with a fervor, never seen before.

It began with isolated protests. As early as June 1965, Richard Steinke, a West Point graduate in Vietnam, refused to board an aircraft taking him to a remote Vietnamese village. "The Vietnamese war," he said, "is not worth a single American life." Steinke was court-martialed and dismissed from the service. The following year, three army privates, one black, one Puerto Rican, one Lithuanian-Italian-all poor-refused to embark for Vietnam, denouncing the war as "immoral, illegal, and unjust." They were court-martialed and imprisoned.

In early 1967, Captain Howard Levy, an army doctor at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, refused to teach Green Berets, a Special Forces elite in the military. He said they were "murderers of women and children" and "killers of peasants." He was court-martialed on the ground that he was trying to promote disaffection among enlisted men by his statements. The colonel who presided at the trial said: "The truth of the statements is not an issue in this case." Levy was convicted and sentenced to prison.

The individual acts multiplied: A black private in Oakland refused to board a troop plane to Vietnam, although he faced eleven years at hard labor. A navy nurse, Lieutenant Susan Schnall, was court-martialed for marching in a peace demonstration while in uniform, and for drop ping antiwar leaflets from a plane on navy installations. In Norfolk, Virginia, a sailor refused to train fighter pilots because he said the war was immoral. An army lieutenant was arrested in Washington, D.C., in early 1968 for picketing the White House with a sign that said: " 120,000 American Casualties-Why?" Two black marines, George Daniels and William Harvey, were given long prison sentences (Daniels, six years, Harvey, ten years, both later reduced) for talking to other black marines against the war.

As the war went on, desertions from the armed forces mounted. Thousands went to Western Europe-France, Sweden, Holland. Most deserters crossed into Canada; some estimates were 50,000, others 100,000. Some stayed in the United States. A few openly defied the military authorities by taking "sanctuary" in churches, where, surrounded by antiwar friends and sympathizers, they waited for capture and court-martial. At Boston University, a thousand students kept vigil for five days and nights in the chapel, supporting an eighteen-year old deserter, Ray Kroll.

Kroll's story was a common one. He had been inveigled into joining the army; he came from a poor family, was brought into court, charged with drunkenness, and given the choice of prison or enlistment. He enlisted. And then he began to think about the nature of the war.

On a Sunday morning, federal agents showed up at the Boston University chapel, stomped their way through aisles clogged with students, smashed down doors, and took Kroll away. From the stockade, he wrote back to friends: "I ain't gonna kill; it's against my will...." A friend he had made at the chapel brought him books, and he noted a saying he had found in one of them: "What we have done will not be lost to all Eternity. Everything ripens at its time and becomes fruit at its hour."

The GI antiwar movement became more organized. Near Fort Jackson, South Carolina, the first "GI coffeehouse" was set up, a place where soldiers could get coffee and doughnuts, find antiwar literature, and talk freely with others. It was called the UFO, and lasted for several years before it was declared a "public nuisance" and closed by court action. But other GI coffeehouses sprang up in half a dozen other places across the country. An antiwar "bookstore" was opened near Fort Devens, Massachusetts, and another one at the Newport, Rhode Island, naval base.

Underground newspapers sprang up at military bases across the country; by 1970 more than fifty were circulating. Among them: About Face in Los Angeles; Fed Up! in Tacoma, Washington; Short Times at Fort Jackson; Vietnam Gl in Chicago; Graffiti in Heidelberg, Germany; Bragg Briefs in North Carolina; Last Harass at Fort Gordon, Georgia; Helping Hand at Mountain Home Air Base, Idaho. These newspapers printed antiwar articles, gave news about the harassment of GIs and practical advice on the legal rights of servicemen, told how to resist military domination.

Mixed with feeling against the war was resentment at the cruelty, the dehumanization, of military life. In the army prisons, the stockades, this was especially true. In 1968, at the Presidio stockade in California, a guard shot to death an emotionally disturbed prisoner for walking away from a work detail. Twenty-seven prisoners then sat down and refused to work, singing "We Shall Overcome." They were court-martialed, found guilty of mutiny, and sentenced to terms of up to fourteen years, later reduced after much public attention and protest.

The dissidence spread to the war front itself. When the great Moratorium Day demonstrations were taking place in October 1969 in the United States, some GIs in Vietnam wore black armbands to show their support. A news photographer reported that in a platoon on patrol near Da Nang, about half of the men were wearing black armbands. One soldier stationed at Cu Chi wrote to a friend on October 26, 1970, that separate companies had been set up for men refusing to go into the field to fight. "It's no big thing here anymore to refuse to go." The French newspaper Le Monde reported that in four months, 109 soldiers of the first air cavalry division were charged with refusal to fight. "A common sight," the correspondent for Le Monde wrote, "is the black soldier, with his left fist clenched in defiance of a war he has never considered his own."

Wallace Terry, a black American reporter for Time magazine, taped conversations with hundreds of black soldiers; he found bitterness against army racism, disgust with the war, generally low morale. More and more cases of "fragging" were reported in Vietnam-incidents where servicemen rolled fragmentation bombs under the tents of officers who were ordering them into combat, or against whom they had other grievances. The Pentagon reported 209 fraggings in Vietnam in 1970 alone.

Veterans back from Vietnam formed a group called Vietnam Veterans Against the War. In December 1970, hundreds of them went to Detroit to what was called the "Winter Soldier" investigations, to testify publicly about atrocities they had participated in or seen in Vietnam, committed by Americans against Vietnamese. In April 1971 more than a thousand of them went to Washington, D.C., to demonstrate against the war. One by one, they went up to a wire fence around the Capitol, threw over the fence the medals they had won in Vietnam, and made brief statements about the war, sometimes emotionally, sometimes in icy, bitter calm.

In the summer of 1970, twenty-eight commissioned officers of the military, including some veterans of Vietnam, saying they represented about 250 other officers, announced formation of the Concerned Officers Movement against the war. During the fierce bombings of Hanoi and Haiphong, around Christmas 1972, came the first defiance of B-52 pilots who refused to fly those missions.

On June 3, 1973, the New York Times reported dropouts among West Point cadets. Officials there, the reporter wrote, "linked the rate to an affluent, less disciplined, skeptical, and questioning generation and to the anti-military mood that a small radical minority and the Vietnam war had created."

But most of the antiwar action came from ordinary GIs, and most of these came from lower-income groups-white, black, Native American, Chinese.

A twenty-year-old New York City Chinese-American named Sam Choy enlisted at seventeen in the army, was sent to Vietnam, was made a cook, and found himself the target of abuse by fellow GIs, who called him "Chink" and "gook" (the term for the Vietnamese) and said he looked like the enemy. One day he took a rifle and fired warning shots at his tormentors. "By this time I was near the perimeter of the base and was thinking of joining the Viet Cong; at least they would trust me. " Choy was taken by military police, beaten, court-martialed, sentenced to eighteen months of hard labor at Fort Leavenworth. "They beat me up every day, like a time clock." He ended his interview with a New York Chinatown newspaper saying: "One thing: I want to tell all the Chinese kids that the army made me sick. They made me so sick that I can't stand it."

A dispatch from Phu Bai in April 1972 said that fifty GIs out of 142 men in the company refused to go on patrol, crying: "This isn't our war!" The New York Times on July 14,1973, reported that American prisoners of war in Vietnam, ordered by officers in the POW camp to stop cooperating with the enemy, shouted back: "Who's the enemy?" They formed a peace committee in the camp, and a sergeant on the committee later recalled his march from capture to the POW camp:

Until we got to the first camp, we didn't see a village intact; they were all destroyed. I sat down and put myself in the middle and asked myself: Is this right or wrong? Is it right to destroy villages? Is it right to kill people en masse? After a while it just got to me.

Pentagon officials in Washington and navy spokesmen in San Diego announced, after the United States withdrew its troops from Vietnam in 1973, that the navy was going to purge itself of "undesirables"- and that these included as many as six thousand men in the Pacific fleet, "a substantial proportion of them black." All together, about 563,000 GIs had received less than honorable discharges. In the year 1973, one of every five discharges was "less than honorable." indicating something less than dutiful obedience to the military. By 1971, 177 of every 1,000 American soldiers were listed as "absent without leave," some of them three or four times. Deserters doubled from 47,000 in 1967 to 89,000 in 1971.

One of those who stayed, fought, but then turned against the war was Ron Kovic. His father worked in a supermarket on Long Island. In 1963, at the age of seventeen, he enlisted in the marines. Two years later, in Vietnam, at the age of nineteen, his spine was shattered by shellfire. Paralysed from the waist down, he was put in a wheelchair. Back in the States, he observed the brutal treatment of wounded veterans in the veterans' hospitals, thought more and more about the war, and joined the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. He went to demonstrations to speak against the war. One evening he heard actor Donald Sutherland read from the post-World War I novel by Dalton Trumbo, Johnny Got His Gun, about a soldier whose limbs and face were shot away by gunfire, a thinking torso who invented a way of communicating with the outside world and then beat out a message so powerful it could not be heard without trembling.

'Sutherland began to read the passage and something I will never forget swept over me. It was as if someone was speaking for everything I ever went through in the hospital.... I began to shake and I remember there were tears in my eyes.

Kovic demonstrated against the war, and was arrested. He tells his story in Born on the Fourth of July:

They help me back into the chair and take me to another part of the prison building to be booked. "What's your name?" the officer behind the desk says.

"Ron Kovic," I say. "Occupation, Vietnam veteran against the war."

"What?" he says sarcastically, looking down at me.

"I'm a Vietnam veteran against the war," I almost shout back.

"You should have died over there," he says. He turns to his assistant "I'd like to take this guy and throw him off the roof."

They fingerprint me and take my picture and put me in a cell. I have begun to wet my pants like a little baby. The tube has slipped out during my examination by the doctor. I try to fall asleep but even though I am exhausted, the anger is alive in me like a huge hot stone in my chest. I lean my head up against the wall and listen to the toilets flush again and again.'

Kovic and the other veterans drove to Miami to the Republican National Convention in 1972, went into the Convention Hall, wheeled themselves down the aisles, and as Nixon began his acceptance speech shouted, "Stop the bombing! Stop the war!" Delegates cursed them: "Traitor!" and Secret Service men hustled them out of the hall.

Extracted from a People's History of the United States

https://libcom.org/library/soldiers-opposition-to-vietnam-war-zinn